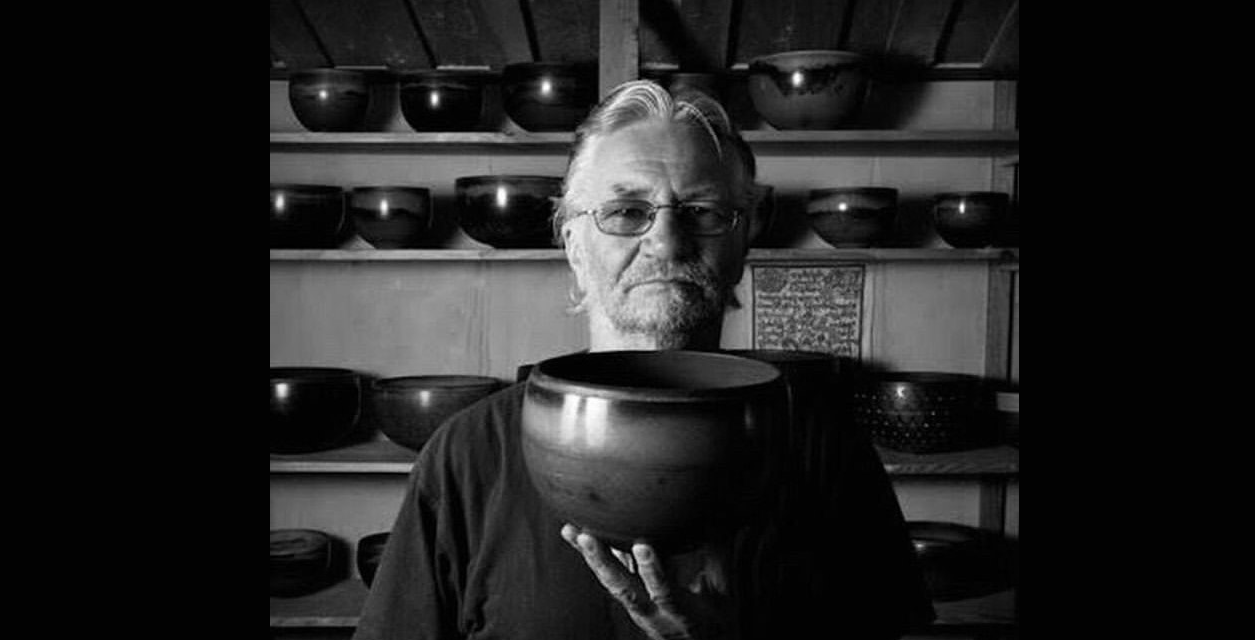

Petrus Spronk

War is war. It usually starts with a few careless remarks thrown across the border. They follow this up by the tossing of a few bricks, then a table and some chairs, then they lob the whole caboodle at the perceived enemy across the border, and she is on for young and old but mainly for those in between. However, everyone is affected in some way, even a little kid of about 5 years old. And I was that little kid.

I was born in Holland just before the war which meant that I was 6 (and therefore able to remember 1945) when that party was over for the aggressors. The aggressors which were very pissed off towards the end. And they certainly let us know. And how did they do that?

Why am I thinking about something like this now? Well, a couple of months ago as a result of my involvement with Words in Winter, my contribution was to create an event where I would be interviewed by Maia Irell but unfortunately her father was dying so she had to rush off to the USA and I had to implement plan B in which Morgan, the director of Radius Art Gallery, stepped up to the plate.

I created a set of que cards so I wouldn’t forget any of the stories, however, when I came home that evening I found that I had hardly looked at my cards. I can vaguely remember the start of the event when I told the audience that I lived for the first years of my life in an atmosphere of fear. And that occasionally the fear returns. Brushes past you, creating a feeling of panic at the most unexpected moments, set off by a few bars of music, an image, a smell or a face on the tram.

What I forgot to tell the folks gathered for that Words in Winter chat, was that the events which should have happened in nightmares, happened in real life. Like in ordinary everyday life.

Next door lived a family with a little girl, my playmate. One night while families sat, huddled in their cellars waiting for the the ground to shake or the bombing to pass, one of the bombs hit the neighbour’s house with more than the shaking of the ground. The next morning we didn’t need to knock on the door to look into their lounge room. Their front door hung suspended from its hinges and the side wall of the house was bombed into a gaping hole allowing me to look directly into their house. However, no one was killed. But when the house got fixed up we were always reminded of this near miss by the scar left behind in the brick work.

But wait, there is more. As a result of this event, the little girl, my friend, was invited to be bussed to the east of Holland for a stay on a farm. On the way to their destination, the bus got strafed. Every child in that bus died.

Our house was opposite a canal, near a bridge. On the side of the bridge, horizontally, hung a long pole with a steel hook at one end of it. This was to assist in the rescue of people who had fallen into the water. Only during this time it was used to keep a soldier, who had been pushed into the water, under it until he drowned. The punishment was swift. The people who lived at the section where the soldier was shoved into the water, were given twenty minutes to gather their stuff and told to leave their house. Their house, including a lifetime of memories, was torched. I remember the sad procession of people walking past our house with their carts, wheelbarrows and bikes, anything with wheels, all laden with their belongings

I also remember that occasionally there would appear a small bunch of flowers in ‘the black ashes of memory’ of that terrible event.

The occupiers were able to up the ante. For instance, around the corner, the canal had a side arm with a lawn area and the cathedral on one side and the primary school run by the church on the other. One day a Dutch informer cycling along the road got shot off his bike. This is what I overheard from the adults as necessary information to the story.

Soon thereafter, I was walking along our street with my aunty when we were stopped by a soldier and re-directed. I strongly remember the gun he wore. He told us to go to the next corner where a group of very nervous locals were gathered . A few soldiers stopped them from leaving and forced them to watch another group of soldiers executing five locals with a pistol to the head. Bang, bang. Another five lives snuffed out uselessly. And forever a horrid memory for more than those who were forced to watch it.

These were just a few stories recalled by me as a five year old. However, it describes enough to fill a book of biblical proportions.

War is War, and when the war is over it will, for a long time after, throw a long dark shadow, not only over the fields of conflict, but also over the collective consciousness of the populace.

And, regardless, all that stuff is still going on today.

Petrus Spronk (art@petrusspronk.com) is a local author and artist who contributes a monthly column to The Wombat Post.