He bought the house in 1986 and made it his. Practical, optimistic and self contained – like the man himself. It has a living space, a light filled studio with a gallery converted from a shipping container out the back, along with the vegie patch you look over from the window. The rabbits on the trip out looked like they could be a pest. He smiles ruefully.

Petrus is in his tee shirt and jeans with tousled grey hair and glasses. He is friendly and thoughtful and interested in talking about art, creativity and how they develop and intersect with life. Sitting outside with him on a warm late spring day, it’s a long way and a long life from Haarlem in the 1940s. From trade school learning to make fine pastries, to a successful Australian ceramicist and sculptor. One who had over 150 people at his 80th birthday at the Palais last year and has had many, many exhibitions here and overseas. His work is represented by the Australian Galleries in Collingwood – a significant Australian ceramicist.

Petrus is probably best known for his finely burnished black ceramic bowls influenced by the work of the native Americans – an insight from wandering the world when he was a young man. For Petrus the black creates a tension, it both absorbs the light and reflects it through the burnishing and polishing. It is an old technique refined for a contemporary presentation.

He has combined the native American practice with subtle motifs and influences from other cultures and his own experiments and accidents – including learning to break and reassemble bowls. A technique he discovered early on living in the Flinders ranges when he was in too much of a hurry and a bowl broke and the shard fell into the kiln and changed from carbon black back to terracotta in the intense heat.

The experience of other cultures has been central in forming Petrus. Like many migrants he has never been completely at home in Australia or in the country of his birth. Somewhere in between. Looking at the world a little differently than others.

As a young man, he started travelling the world on a six month grant to visit the United States from the Western Australian Craft Council. As his grant came to an end he made the decision not to come back and sold his return ticket to Australia to someone else. He didn’t come back to Australia for eight years.

He travelled from place to place, following his instincts, often influenced by word of mouth about places and artistic ideas and practices he might like. He was fascinated by traditional, manual techniques, using local materials, forms and motifs. He found Ireland and Greece magical places and Korea has continued to influence his work.

He has written a book on his Korean odyssey. Sitting outside he tells the story of his routine there, working in the studio, preparing exhibitions, visiting the temple on Sunday and giving talks on Monday. At the temple, he became friends with a Zen monk who invited him to meet a Zen master. Apparently, not an everyday event.

Petrus says he was allowed to ask the Zen master one question. He followed a group through a low door. Waited for his turn. The nod came from the master and he asked what he could do to be a better artist. One word – ‘attention’ and then he was waved off.

Petrus admits that for a moment he thought he’d been told-off for not paying enough attention – something that used to happen to him at school. But the word has stayed with him. Attention to the moment, to the work, to the process, to the surroundings. Attention matters to him. When everything goes well, time flows effortlessly.

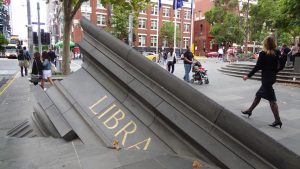

He says when he is considering creating a piece of public sculpture, he stands in the space where the piece is going and asks himself ‘what is needed here?’ He doesn’t start with predetermined answers. He pays attention to the space at the time, in the moment.

He has an ongoing interest in architecture and art. He developed the idea for architectural fragments following an incidental comment from his mother. On a visit to Adelaide she told him that, as a child, he’d been interested in building things in the sandpit.

He developed the sand pit idea of mirroring parts of surrounding buildings in streetscapes using ‘brickies’ sand and then sculpting fragments with a knife. His brother, a builder gave him give advice about the best sand to use.

Petrus writes about life and art as well. He started with a letter to the Advocate about the Daylesford Art Show put on in the then Pantechnicon gallery in Vincent Street 30 years ago. The Advocate editor Ken Robbins liked it enough that Petrus became a regular columnist. With the decline of the Advocate he now has a monthly column in the Wombat Post.

But time and tide has left its mark. For the past 12 years Petrus has been learning to live with Parkinson’s Disease. His walk has become more stylised and there are some things he can’t do as well. But he retains an optimism about life and work.

Curse and gift, the Parkinson’s Disease has produced an innovative and original evolution of his ceramic work for Petrus to unveil. One that brings together many of the themes and motifs of his previous work in a new form.

Petrus continues to have many friends and admirers in Daylesford and further abroad, including former students. He still remembers the first time he came to Daylesford and went to the Sunday Market straight from the solitary, red, arid Flinders Ranges. The green, beautiful, lush surroundings. The community and the people. This was the place he wanted to be. More than thirty years later he still has projects and proposals he’d like the community to take up.